|

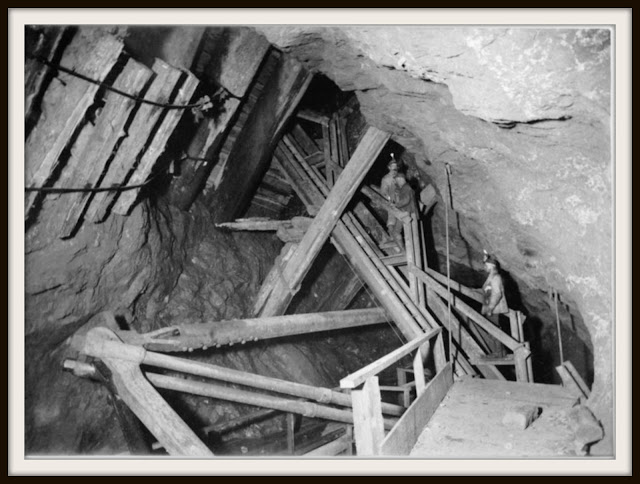

| Quincy Mining Company - underground view of a miner perched on mass copper. Note the candle for light. Courtesy LOC |

The copper mines of the Keneewaw (pronounced KEY-wa-naw). [1] Peninsula brought Maytor Healy from Ireland to Michigan in 1858, he was 40 years old. At the time of his arrival there where many active mines in both the Upper Peninsula and the Goebic Range around Marquette. Initially, before Nellie and the children joined him, Maytor may have worked any of these mines but for certain he was working for the Quincy Mining Company and living on their Quincy property, located on the hill above Hancock, by 1862 when he sent money to his family so they could join him in October of that year.

|

| The failure of Ireland's potato crop in 1845 was especially severe in southern County Cork, including the Beara Peninsula. In the mid- 1840s many miners headed for the new mines in Michigan's Copper Country. A comparison of the names in the Allihies Mine payroll records, and the Griffith's Valuation for the mining area with those in the federal census for Keweenaw, Declarations of Intent to become a U.S. citizen, and the Quincy Mining Company records shows a strong connection with the Minesota, Cliff, and Quincy Mines.[9] |

On the north side of Portage Lake, above Hancock, stood the Quincy, Pewabic and Franklin mines. At the time of Maytor's arrival they were in major production, hiring 200 men that year. Employment at the Quincy mine jumped to 469 men in 1860 and to 583 in 1861.

At the time of his arrival in 1858, the Quincy Mining Company had bunkhouses for their unmarried employees, located on the hillside between what is now Hancock and the Quincy mine location on top of the hill.

We know from the 1870-80 US Census records that Maytor Healy was a miner. There are two contempory definitions of the job title "miner". In it's narrowest sense, a miner is someone who works at the rock face; cutting, blasting, or otherwise working and removing the rock. In a broader sense, a "miner" is anyone working with a mine, not just a worker at the rock face. [5] The nineteenth-century, Upper Peninsula mining companies (Quincy, Franklin, Pewabic) narrowly defined the job of "miner" as being only the men who drilled and blasted rock. That class of worker reserved the term for themselves because it signaled their higher status among underground laborers. Men performing other tasks had other titles. [2, pg. 23] Indications are that Maytor was a skilled experienced miner and he worked below ground.

|

| Miners in the Quincy Mine, Michigan 1870 |

"Miners employed sledge hammers, hand drills and powder to open up all parts of a mine. Because hand drilling was slow, skilled miners first read the mine rock and placed the shot holes where the one miner held the drill's sharpened chisel bit against the rock face. His partner, or partners, then hammered the drill home with eight-pound sledges. After each strike, the holder lifted the drill just a bit and turned it slightly so that the next blow cut a better chip. Since the angle and location of the holes differed from one to the next, miners needed the physical dexterity to swing their hammers through a variety of arcs, always striking the drill head squarely while missing the holder's hands and wrists. The number of men on a drill team varied, depending on the size of the opening. In a large stope, often one man held the drill steel while two men wielded sledges. In a small drift, as little as six feet high and five feet wide, there was no room for a third man, so one man "jacked" (hammered) the drill while his partner held it.

"Using a succession of hand steels of increasing length, miners drove shot holes to a depth of perhaps four feet. As the end of the shift neared, they cleared the holes of chips and charged them with explosives and fuses. For the first two decades the mines used black powder made up of saltpeter, sulfur and charcoal. Mines stored explosives in magazines on the surface, and some mines transported powder underground on Sundays, when fewer men would be around if a big, accidental explosion occurred. The mining teams had lockboxes underground to store explosives and drew from their own powder kegs to charge holes.

|

| The holes are drilled and and charged, now ready to light the fuses. |

After lighting fuses, they retreated a safe distance and waited for the explosions. When a burning fuse ignited a charge, the explosive detonated at a rate of about 1500 feet per second. The expanding gases heaved the rock, breaking it free. From their place of retreat, the miners counted the blasts. If they set eight charges and heard eight explosions, they were done for the day. If not, they had a missed hole- a charge had not fired. In that case, they waited around long enough for it to be safe to go back in and try to fire that hole again. Unexploded charges were accidents waiting to happen and needed to be dealt with." [2]

"When miners discovered a large mass of copper, they drilled and blasted all around it. To free the mass from the last ground holding it, miners tucked full, twenty-five-pound powder kegs around the point of contact and used sandbags to help direct the force of the blast. Copper is a gummy, malleable metal. Explosions do not fracture it, and no machine existed to cut it up as it sat on the mine floor, so men cut it up by hand." [2]

"Knowing how large a piece of copper that man could transport out of the mine, a mining captain drew lines across the mass, showing copper cutters where to part it. One man held a chisel to the copper; others struck its head with sledges. The chisel holder walked the chisel along the cut line, and the tool produced a long chip as it moved from one side of the mass to the other. The men repeated this operation time after time. As the channel deepened, the holder reached for a longer chisel. Finally, the men cut through the bottom of the mass. They parted it again, if necessary, and then others transported the pieces of mass copper to the shaft for hoisting to the surface." [2]

"To light their way underground, each man carried a shift's worth of tallow candles with him, using their extra long wicks to tie them to his belt. He walked along a drift by the light of a candle held to his helmet with a ball of clay. A mining team drilled rock by a light of a few candles spiked to the wall or held to the rock with the clay balls taken from helmets. The men worked in a dim pool of light, and a vast darkness spread from one team of men over to the next. Looking over, a man saw a pinpoint candle flame in the distance, but little in the way of human features."

"Mining Companies almost wholly depended on natural ventilation to move fresh air into and through their mines. Shafts filled with air columns of different heights, coupled with temperature gradients between the surface and the underground, kept the air moving. Certain shafts were downcast and carried a strong draught of fresh air underground. Other shafts served as chimneys. Upcast shafts exhausted stale air, blasting gases, and dust into the atmosphere at grass. For decades the Lake mines resorted very little to mechanical fans to augment their system of natural ventilation, and all the while, experts lauded the mines for their clean and cool air."

1865 - Cutting mass copper at the Quincy mine location. Three miners underground using a chisel and sledge to break up the large piece of copper. A candle burns on the rock ledge on the far left.

Photo courtesy of Mich. Tech. University |

"Knowing how large a piece of copper that man could transport out of the mine, a mining captain drew lines across the mass, showing copper cutters where to part it. One man held a chisel to the copper; others struck its head with sledges. The chisel holder walked the chisel along the cut line, and the tool produced a long chip as it moved from one side of the mass to the other. The men repeated this operation time after time. As the channel deepened, the holder reached for a longer chisel. Finally, the men cut through the bottom of the mass. They parted it again, if necessary, and then others transported the pieces of mass copper to the shaft for hoisting to the surface." [2]

"To light their way underground, each man carried a shift's worth of tallow candles with him, using their extra long wicks to tie them to his belt. He walked along a drift by the light of a candle held to his helmet with a ball of clay. A mining team drilled rock by a light of a few candles spiked to the wall or held to the rock with the clay balls taken from helmets. The men worked in a dim pool of light, and a vast darkness spread from one team of men over to the next. Looking over, a man saw a pinpoint candle flame in the distance, but little in the way of human features."

"Mining Companies almost wholly depended on natural ventilation to move fresh air into and through their mines. Shafts filled with air columns of different heights, coupled with temperature gradients between the surface and the underground, kept the air moving. Certain shafts were downcast and carried a strong draught of fresh air underground. Other shafts served as chimneys. Upcast shafts exhausted stale air, blasting gases, and dust into the atmosphere at grass. For decades the Lake mines resorted very little to mechanical fans to augment their system of natural ventilation, and all the while, experts lauded the mines for their clean and cool air."

"Until the mid-1860s, men transported themselves in and out of a mine. In a vertical shaft, they sometimes rode out of the mine on a rope sling or in a kibble. In an inclined shaft, they hitched rides on rock skips. But wooden ladders remained their principle means of getting to and from work. Rough planks often separated the ladder way from the shaft's adjacent hoisting compartment. Men risked falls from ladders, whose rungs could be damp or slippery or in poor repair. In winter, close to the frigid surface, a ladder might even be covered in ice." [2]

|

| Early underground miners. Note the use of candles. |

"At the end of a shift, underground workers reversed the procedure to get up to grass. Instead of stepping over the rod poised to go down, after each pause of the man-engine rods, they stepped over the rod ready to move up." [2]

|

| Quincy Mine Man-Engine, 1870-80 |

"From the time they left the surface until their return, underground workers toiled nearly ten hours a day. Once underground, most men stayed there for the entire shift. They ate a meal underground, most men stayed there for the entire shift. They ate a meal underground; men carried their victuals below in tin pails and reheated them over candles. The underground was a world unto itself: dark, rough, hazardous, enclosing, steeply pitched, filled with the sounds of hammer blows and the smell of spent blasing powder. It was a place of work with a single purplse: to liberate copper and get it to the surface. Atop the mine, a very different world existed."[2]

|

| Earliest known photograph of the Quincy Shaft - House, view showing No. 1 Winze and Nos. 2-4 shaft houses, 1875, courtesy LOC |

|

| The Quincy Location, Shafts No. 1,2,4 on the right. , courtesy LOC |

The Quincy Mining Company, after its fortunes picked up in the late 1850s, had no intentions of building or controlling its own town. Above Hancock, on Quincy Hill, beginning in 1865 it erected a typical mine location, with many shafts, a full complement of mining structures, a range of company houses, and a single store.

Quincy did, however, support the development of the village of Hancock. Quincy platted and sold lots to help create a town that offered a wide range of housing and services to Quincy employees and others in the area. [4]

|

| Laborers pose outside Quincy Mine Rockhouse 1875, courtesy LOC |

Maytor Healy Sr. and Maytor James Jr. worked in the Quincy mine during this time period. Notice the young boys seated behind on the far right.

|

| Quincy Mine No.4 Rockhouse. Note the Tramroad that led to the Stamp Mill on Portage Lake and the buildings on the left., courtesy LOC |

|

| Enlargement of the previous map - Quincy Hill 1865 |

Notice the company houses located in the planned segregated neighborhoods - Hardscrabble and Limerick (and later, Frenchtown). The captain's office, blacksmith shop, supply office, dry and change house, carpenter shop, clerks house, doctors house, store (for mining employee families), company office, and agents house. The locations of each building, including the mine shafts 1 thru 5, rockhouses, and Tramroad (which led down to the Village of Hancock and the Stamp Mill on Portage Lake) in the above map.

|

| The blacksmiths outside their shop (built in 1860) at the Quincy location, the Rockhouse is in the background on the far left, courtesy LOC |

Due to the time-frame of 1875-80, that this photo was taken, and because Maytor Healy worked underground in the Quincy mines, it is possible that Maytor and his son, Maytor James Healy are in this photo. Maytor Sr. would have been between 58 and 63 years of age, Maytor James Healy would have been between 11 and 16 years old.

|

| The Quincy Mine Office, located at the Quincy location above Hancock. |

|

| Samuel B Harris, superintendent of the Quincy Mining Company Mines in Hancock - 1883 - Men of Progress, pg. 253 |

_________________________________________________________________

Sources

[1] From the Emerald Isle to the Copper Island; The Irish in the Michigan Copper Country 1845-1920, by William H Mulligan Jr.

[2] Larry D Lankton, Hollowed Ground: Copper Mining and Community Building on Lake Superior, Wayne State University; Google Books

[3] Church of the Resurrection, 900 Quincy St., Hancock Illinois

[4] Historic American Engineering Record Collection, Library of Congress

[5] A Glossary of the Mining and Mineral Industry, Albert H. Hill

[6] Daniel Sampson Healy, an Oral History

[7] Michigan Technological University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections

[8] Donald G Magill, Canvas of St. Joseph Graveyard, Hancock Houghton Michigan

[9] Who Where My Ancestors? by Riobard O' Dwyer

[10] New Hibernia Review, Irish Immigrants in Michigan's copper Country , William H. Mulligan, 2001, University of St. Thomas; Center for Irish Studies

[11] Memories of Edward Murphy, recorded 20 July 2013

[12] Irish Immigrants in Michigan's Copper Country, William H. Mulligan

[13] Beyond the Boundaries, Life and Landscape at the Lake Superior Copper Mines, 1840-1875, by Larry Lankton